Jewish Festivals

(in the order in which they occur, click on the links):

- Rosh Hashana

- Yom Kippur

- Sukkot

- Chanukah

- Shemini Atzeret & Simchat Torah

- Tu Bishvat

- Purim

- Pesach

- Shavuot

Rosh Hashana

Rosh Hashanah is known as the Jewish new year although it actually occurs on the 1st of the 7th month in the Jewish lunar calendar. The Torah refers only to a day’s holiday on that date with the blowing of a horn. It was in the first century that the rabbis began to celebrate this day as a new year as it co-incided with the start of the agricultural cycle.

Our traditions at this time of year include blowing a shofar -a ram’s horn, reading the story of Abraham and Isaac and and eating apples and honey or honey cake to celebrate the sweetness of life. The challah – the plaited loaf customarily eaten every Shabbat – is made in a round shape to represent the cycle of life. We engage in ‘teshuvah’ – the spiritual practice of ‘repentance’ which means to consider whom we may have wronged in the past year, to apologise and seek their forgiveness and consider how we can change our behaviours for the next year.

The day also marks the start of the High Holidays and the ten day period known as the Days of Awe running up to Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. During this period we consider the image of the Book of Life which is written on Rosh Hashanah and closed on Yom Kippur. A literal interpretation of this idea is that the book holds the names of those who will love and die in the next year, introducing questions about fate and preordination. It can also be taken as a metaphor and a reminder of the fragility of life and the wisdom of making positive changes sooner than later.

The ritual of ‘tashlich’ which is a symbolic throwing away of our sins into body of flowing water and like in many traditions on New Year there is a sense of a new start. The traditional Rosh Hashanah greetings are L’Shana Tovah Tikateivu meaning ‘may you be inscribed [in the Book of Life] for a good year’ and Shana Tovah U’metukah meaning ‘have a good and sweet New year’.

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur means Day of Atonement and is the most sacred day in the Jewish Calendar also called the Sabbath of Sabbaths. The process of teshuvah (repentance) which begins on Rosh Hashanah ends on Yom Kippur. Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur and the days in between are known as the Days of Awe – the Yamim Noraim or the High Holidays. The Torah instructs that this day is to fall on the tenth day of the 7th month.

Yom Kippur is a serious, solemn festival for which involves a 24-hour fast and praying in the synagogue on the night of Kol Nidre and all the next day for those who are able to do so. In addition many Jews will avoid wearing leather, perfume and other symbols of luxury. It is also traditional to wear something white. Despite the fact that the traditions are onerous, Yom Kippur is the most observed day of the Jewish calendar and many otherwise non-observant Jews choose to mark this day with a fast for all or part of the day and synagogue attendance.

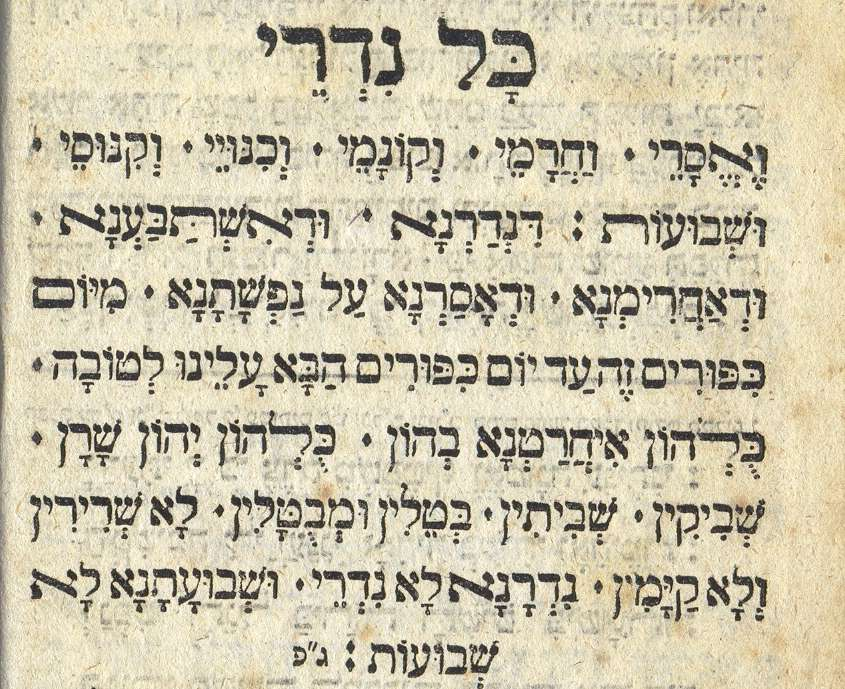

There are services throughout Yom Kippur with the first one being Kol Nidre. Jewish holidays commence at sundown so this take place in the evening just before Yom Kippur officially begins. This means that practically the fast has to be extended a little past the twenty four hours! Kol Nidre is the re-enactment of metaphoric proceedings in a legal court in which we publicly annul any vows made to God between now and the next Kol Nidre. This applies only to vows made to God not to other people.

The service starts with the words of the Kol Nidrei prayer being sung and repeated three times. The haunting melody of Kol Nidre comes from a body of music called MiSinai (“of Sinai”) melodies, which originated in Germany between the 11th and 15th centuries. These melodies became “attached” to prayers of the Ashkenazic Jews and were passed down through the generations.

Here is a wonderful rendition of Kol Nidre.

The Biblical book of Jonah is read on Yom Kippur. The Vidui prayer is a collective confession. It is an acrostic symbolising that humans are capable of all kinds of wrong behaviour from A right through to Z.

At the end of the final service of the day, the end of the fast is announced with a long blast on the shofar. After Yom Kippur it is a tradition to eat together with family of friends as a break-fast meal.

Traditional Yom Kippur greetings include “I wish you well over the fast”, “have an easy fast’ or ‘have a meaningful fast’ as well as the greeting ‘G’mar Chatima Tova’ which means ‘May you be sealed in the Book of Life’.

Sukkot

Sukkot falls on the 15th day of the 7th Jewish month of Tishrei. It focuses on themes of survival and God’s protection. The word sukkot or succot means booth referring to a temporary structure like a tent. One way to celebrate is to construct a Sukkah in the garden or in the synagogue grounds made or decorated with fruit and branches and eat at least one meal in it. For this reason the festival can also be called the Feat of Tabernacles.

The Succah can be plain or highly decorated (as in the photo of the Sukkah of a couple in our community) The Sukkah reminds us of the period when the Israelites were wandering in the desert living in tents. It is also a good time for us to remember and symbolically identify with those who are homeless today. The Sukkah should be a little open to the elements so the stars can be seen if you sleep in it. This is usually achieved by leaving the roof covering (if there is one) either totally or partially open.

Sukkot, in the autumn, combines with the next two festivals, Pesach (Passover) in the spring and Shavuot (Pentecost) in the early summer to form the Three Pilgrimage or Foot festivals, so named because in ancient time it was traditional for people to travel to Jerusalem to celebrate them. The Hebrew word chag (‘ch’ as in loch) relates to those three holidays and is linked to the Arabic word hajj, but these days the word chag is used to describe any of the various Jewish festivals and the words “Chag sameach’ can be used to wish someone a Happy Holidays although that’s not appropriate for the very solemn day of Yom Kippur.

Sukkot is also marked by a ritual that involves four specific types of plants ; branches of palm, myrtle willow ( together forming a ‘lulav’) and a large citrus fruit called an etrog. A blessing is merited and the four items are held together and shaken in six directions (N,S,E,W, Up and Down) to symbolise that God is all around us.

The Hoshanot prayer asks God to save us reinforcing the theme of vulnerability. Sukkot lasts seven days but only the first day is observed as a holy one.

Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah

Shemini Atzeret is both the eight day of Sukkot (when you can use your Sukkah but don’t have to ) and a holiday in its own right referred to in Torah as a holy day. The Hebrew word Atzeret means ‘assembly’ but its root for in Hebrew is ‘stop’ as if the Torah was suggesting to people to extend their stay in Jerusalem with some extra days! It is a day to enjoy extra time in spiritual practice.

Simchat Torah is a day on which we celebrate and honour the Torah although the day itself is not referred to in the Torah!

Throughout the year we read the Torah in a cycle. We start at Bereshit (the Book of Genesis) and end with Devarim (the book of Deuteronomy). Simchat Torah marks the end of that cycle and the beginning of a new one and originated in the fifteenth century. It is a party like festival with the Torah scrolls being carried around the congregation seven times with song and dancing. Members of the congregation are particularly honoured and given the role of reading the last words of the Torah and the first words in the new cycle. The festival of Sukkot is like the full stop at the end of the High Holidays as we start a new cycle and a New Year.

Chanukah

The eight-day Jewish celebration known as Chanukah (also spelt Hannukah) commemorates the rededication during the second century B.C. of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. According to legend Jews had risen up against their Greek-Syrian oppressors in the Maccabean Revolt. Chanukah, which means “dedication” in Hebrew, begins on the 25th of Kislev on the Hebrew calendar and usually falls in November or December. Often called the Festival of Lights, the holiday is celebrated with the lighting of the menorah or chanukiah, traditional food, games and gifts.

The story goes that the Jews could only have regained the temple by a miracle. Part of restoring the mess the Hellenists made in the temple was to relight the menorah – the large seven branched candelabra that should always have been lit in front of the Ark of the Covenant. However they could only find one day’s worth of the necessary oil. They decided to light the menorah anyway and found that, miraculously, it lasted for all eight days.

Today we celebrate that miracle by lighting a candle for every night for the eight days of Chanukah. It is often said that the true miracle is not that the oil inexplicably stretched that far but that they went ahead and lit the menorah not knowing that it would! The story historically allows the turning of an account of a military victory into a festival of lights at a time other cultures would have such a festival as winter approached.

The chanukiah – the special menorah used for this festival actually holds nine candles as one is used as the shamas (helper) to light the others. An extra candle is lit each night until all eight burn at the same time. Modern chanukiah come in all designs from traditional silver to sleek and modern and even in the shape of toy trains for children ( and adults who like toy trains!). It is traditional to place them in a window to publicise the miracle. Families will play a spinning top game with a four sided top known as a dreidel which is embellished with four letters representing yiddish words. It was common to give gifts of coins – now the tradition may be to give bags of chocolate coins or, given that the festival occurs close to the Christian celebration of Christmas, a gift. But many children still like the money!

The traditional food at Chanukah is all fried in oil as a reference to the miracle. Latkes (potato fritters) – or sufganyiot (doughnuts) are common. There is no religious observance to this festival which is entirely home and family based and, unlike the other major holidays, work carries on during this minor festival.

The lighting of the Chanukah candles is usually accompanied by the song Maoz Tzur. Here is a lovely version of it sung by cantors from various congregations across Toronto in Canada.

Tu Bishvat

Tu BiShvat is a holiday occurring on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shevat . It is also called Rosh HaShanah La’Ilanot ) literally “New Year of the Trees”. In contemporary Israel, the day is celebrated as an ecological awareness day, and trees are planted in celebration. Like many festivals this has its origin in the agricultural cycle and the rabbis established it as a general birthday for trees regardless of when they were planted. This enabled compliance with a commandment in the Torah that the fruit of trees was forbidden for the first three years.

On Israeli kibbutzim, Tu BiShvat is celebrated as an agricultural holiday. For anyone concerned about the environment the festival has become an opportunity to think about our stewardship of the earth.

Purim

Purim is a minor but important festival which commemorates the saving of the Jewish People from annihilation at the hands of an official of the Achaemenid Empire named Haman, as it is recounted in the Book of Esther (usually dated to the 5th century BCE). The book, known in scroll form as the Megillah, recounts how the Jewish Esther became the Queen and saved the Jewish people.

The story has it all – rivalry and beauty pageants and can also be seen as a story that retells the real life rivalry between the Israelites and an ancient people call the Amalakites.

Purim is very much a child-centred festival with fancy dress the rule of the day – for adults as well as children! For adults, Purim is the one occasion when drinking alcohol is encouraged. One of the serious obligations is to hear the megillah – the scroll containing the Esther story being read. Children are encouraged to make noise with rattles and stamping feet and to hiss and boo every time they hear the name of the ‘baddy’ Haman. Purim is time for a play or ‘spiel’. Traditional food is hamantaschen, baked cookies with three corners and filling representing the pockets of Haman. Another custom is ‘misloach manot’ – the giving of gifts of food.

Pesach

Pesach, also called Passover, is a major Jewish holiday, one of the three pilgrimage festivals, that celebrates the Biblical story of the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt. Pesach starts on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan which is considered the first month of the Hebrew year. (Confusingly, the Jewish New Year – Rosh Hashana – occurs in the 7th month).

Pesach occurs in the early spring usually around the same time as the Christian Easter which always falls on the first Sunday after first the full moon following the vernal equinox. As a consequence, Easter does not have a fixed date but is proximate to the full moon, which coincides with the start of Passover on the 15th of the lunar Hebrew month of Nissan.

The word Pesach or Passover can also refer to the Korban Pesach, the paschal lamb that was offered when the Temple in Jerusalem stood; to the Passover Seder, the ritual meal on Passover night; or to the Feast of Unleavened Bread. One of the biblically ordained Three Pilgrimage Festivals, Passover is celebrated for seven days in Israel and for eight days among the Jewish diaspora, In the Bible, the seven-day holiday is known as Chag HaMatzot, the feast of unleavened bread (matzah).

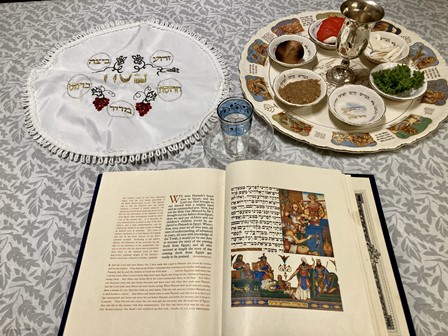

As well as recounting the story of the Israelites escape from slavery, Pesach is also a time to consider those who are in forms of slavery today and those who are refugees or fleeing harm. The central part of the celebration is a meal called a Seder which includes a number of symbolic elements before and after the actual meal which helps us to retell the story.

Before and after the Seder meal – which is usually held with family and guests around the table or in a community setting – the Haggadah is read. The Haggadah tells the story of the escape from Egypt alongside prayers and commentary – a number of which are sung to traditional tunes. There are many different ‘Haggadot’ (plural). Some are plain text but many are decorated with pictures and engravings. There are ancient, very valuable Haggadot that are in libary and museums collections around the world.

Before the festival begins the tradition is to remove all traces of ‘chametz‘ – leavened bread from the house in reference to the fact that the Israelites, while on their journey out of Egypt, ate only unleavened bread as they were in a rush and did not have time to allow yeast to rise. During the eight days of the Festival observant Jews still avoid food that could be leavened.

The Seder Plate has a number of symbolic items. Pesach the roasted lamb shankbone commemorates the sacrifice made the night before the Israelites left. Many people substitute the vegetarian option of a roasted beetroot. A roasted egg signifies spring time and renewal and stands in for another sacrifice. Maror is a bitter herb – horseradish is often chosen which helps us remember the bitterness of slavery. Charoset is a sweet dip made from apples, nuts, wine and cinnamon and represents the mortar used by the Hebrew slave to make bricks. Karpas is a green vegetable – commonly parsley – eaten to make salves feel like nobility. Cahseret is a second bitter herb such as romaine lettuce. salt where represents the tears and swat of ensalvement. Last but not least there is

Matzah the unleavened bread which has the consistency of a large cracker. At the start of the Seder a piece of matzah called the Afikomen is hidden, usually by the host, and the children are asked to find it before the end of the meal when eating the Afikomen signifies the end of the meal .The tradition is that whoever finds it bargains it for a gift of some sort before handing it over to be eaten by those round the table

Four cups of wine are drunk during the telling of the story, and the ten plagues are commemorated by dipping one’s finger into the wine and letting a drop fall onto a plate.

One the best known parts of the Seder, near the start, is the time when the youngest child present asks the question: “Why is tonight different from all other nights?”

Shavuot

Shavuot commemorates the giving of the Torah to Moses and the Children of Israel on Mount Sinai. The word means ‘weeks’ because it falls exactly seven weeks (actually fifty days) after Pesach. It is one of the three Pilgrimage Festivals or ‘Foot’ Festivals along with Pesach and Sukkot. It falls around the time of the summer harvest when the first fruits are available. It is traditional to read the Biblical book of Ruth because it is also set at the time of the summer harvest and Ruth makes the decision for herself to accept the Torah when she decides to join her mother-in-law’s religion. For this reason Ruth is seen as a model of conversion to Judaism.

Shavuot is traditionally celebrated by holding a ‘tikkun leyl shavuot’ – an all night ( or at least an evening) study session. It is traditional to eat dairy food which means lots of blintz’s with cheese and sour cream or cheese cake. This refers to the fact that the dietary rules came in with the giving of the Torah at which point choosing to eat dairy food became simpler than eating meat.

Tisha B’Av

Tisha B’Av, the 9th day of the month of Av is the saddest day in the Jewish calendar. It is a day on which observant Jews fast, deprive themselves and pray. It is the culmination of the Three Weeks, a period of time during which we mark the destruction of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in 72 CE.

Tisha B’Av is a day of mourning and a fast day. Like all Jewish festivals it starts at sundown on the day before and lasts till sundown. There are a number of restrictions and special prayers are said.